Introduction to Python¶

Written by Luke Chang

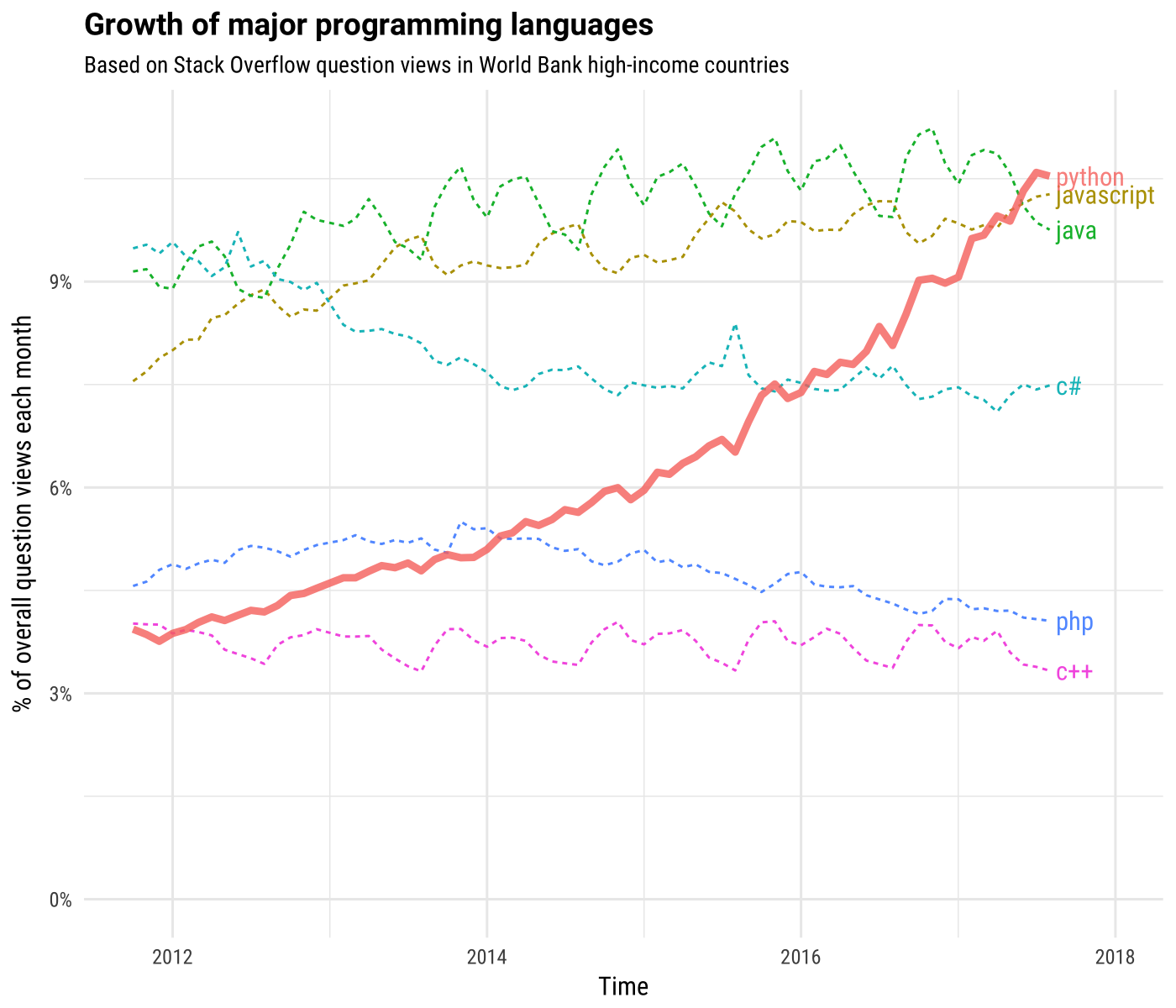

In this notebook we will begin to learn how to use Python. There are many different ways to install Python, but we recommend starting using Anaconda which is preconfigured for scientific computing. Start with installing Python 3.7. For those who prefer a more configurable IDE, Pycharm is a nice option. Python is a modular interpreted language with an intuitive minimal syntax that is quickly becoming one of the most popular languages for conducting research. You can use python for stimulus presentation, data analysis, machine-learning, scraping data, creating websites with flask or django, or neuroimaging data analysis.

There are lots of free useful resources to learn how to use python and various modules. See Jeremy Manning’s or Yaroslav Halchenko’s excellent Dartmouth courses. Codeacademy is a great interactive tutorial. Stack Overflow is an incredibly useful resource for asking specific questions and seeing responses to others that have been rated by the development community.

Jupyter Notebooks¶

We will primarily be using Jupyter Notebooks to interface with Python. A Jupyter notebook consists of cells. The two main types of cells you will use are code cells and markdown cells.

A code cell contains actual code that you want to run. You can specify a cell as a code cell using the pulldown menu in the toolbar in your Jupyter notebook. Otherwise, you can can hit esc and then y (denoted “esc, y”) while a cell is selected to specify that it is a code cell. Note that you will have to hit enter after doing this to start editing it. If you want to execute the code in a code cell, hit “shift + enter.” Note that code cells are executed in the order you execute them. That is to say, the ordering of the cells for which you hit “shift + enter” is the order in which the code is executed. If you did not explicitly execute a cell early in the document, its results are now known to the Python interpreter.

Markdown cells contain text. The text is written in markdown, a lightweight markup language. You can read about its syntax here. Note that you can also insert HTML into markdown cells, and this will be rendered properly. As you are typing the contents of these cells, the results appear as text. Hitting “shift + enter” renders the text in the formatting you specify. You can specify a cell as being a markdown cell in the Jupyter toolbar, or by hitting “esc, m” in the cell. Again, you have to hit enter after using the quick keys to bring the cell into edit mode.

In general, when you want to add a new cell, you can use the “Insert” pulldown menu from the Jupyter toolbar. The shortcut to insert a cell below is “esc, b” and to insert a cell above is “esc, a.” Alternatively, you can execute a cell and automatically add a new one below it by hitting “alt + enter.”

print("Hello World")

Package Management¶

Package managment in Python has been dramatically improving. Anaconda has it’s own package manager called ‘conda’. Use this if you would like to install a new module as it is optimized to work with anaconda.

!conda install *package*

However, sometimes conda doesn’t have a particular package. In this case use the default python package manager called ‘pip’.

These commands can be run in your unix terminal or you can send them to the shell from a Jupyter notebook by starting the line with !

It is easy to get help on how to use the package managers

!pip help install

!pip help install

!pip list --outdated

!pip install setuptools --upgrade

Variables¶

Python is a dynamically typed language, which means that you can easily change the datatype associated with a variable. There are several built-in datatypes that are good to be aware of.

Built-in

Numeric types:

int, float, long, complex

String: str

Boolean: bool

True / False

NoneType

User defined

Use the type() function to find the type for a value or variable

Data can be converted using cast commands

# Integer

a = 1

print(type(a))

# Float

b = 1.0

print(type(b))

# String

c = 'hello'

print(type(c))

# Boolean

d = True

print(type(d))

# None

e = None

print(type(e))

# Cast integer to string

print(type(str(a)))

<class 'int'>

<class 'float'>

<class 'str'>

<class 'bool'>

<class 'NoneType'>

<class 'str'>

Math Operators¶

+, -, *, and /

Exponentiation **

Modulo %

# Addition

a = 2 + 7

print(a)

# Subtraction

b = a - 5

print(b)

# Multiplication

print(b*2)

# Exponentiation

print(b**2)

# Modulo

print(4%9)

# Division

print(4/9)

9

4

8

16

4

0.4444444444444444

String Operators¶

Some of the arithmetic operators also have meaning for strings. E.g. for string concatenation use

+signString repetition: Use

*sign with a number of repetitions

# Combine string

a = 'Hello'

b = 'World'

print(a + b)

# Repeat String

print(a*5)

HelloWorld

HelloHelloHelloHelloHello

Logical Operators¶

Perform logical comparison and return Boolean value

x == y # x is equal to y x != y # x is not equal to y x > y # x is greater than y x < y # x is less than y x >= y # x is greater than or equal to y x <= y # x is less than or equal to y```

X |

not X |

|---|---|

True |

False |

False |

True |

X |

Y |

X AND Y |

X OR Y |

|---|---|---|---|

True |

True |

True |

True |

True |

False |

False |

True |

False |

True |

False |

True |

False |

False |

False |

False |

# Works for string

a = 'hello'

b = 'world'

c = 'Hello'

print(a==b)

print(a==c)

print(a!=b)

# Works for numeric

d = 5

e = 8

print(d < e)

False

False

True

True

Conditional Logic (if…)¶

Unlike most other languages, Python uses tab formatting rather than closing conditional statements (e.g., end).

Syntax:

if condition:

do something

Implicit conversion of the value to bool() happens if

conditionis of a different type than bool, thus all of the following should work:

if condition: do_something elif condition: do_alternative1 else: do_otherwise # often reserved to report an error # after a long list of options ```

n = 1

if n:

print("n is non-0")

if n is None:

print("n is None")

if n is not None:

print("n is not None")

n is non-0

n is not None

Loops¶

for loop is probably the most popular loop construct in Python:

for target in sequence: do_statements

However, it’s also possible to use a while loop to repeat statements while

conditionremains True:

while condition do: do_statements

string = "Python is going to make conducting research easier"

for c in string:

print(c)

P

y

t

h

o

n

i

s

g

o

i

n

g

t

o

m

a

k

e

c

o

n

d

u

c

t

i

n

g

r

e

s

e

a

r

c

h

e

a

s

i

e

r

x = 0

end = 10

csum = 0

while x < end:

csum += x

print(x, csum)

x += 1

print(f"Exited with x=={x}")

0 0

1 1

2 3

3 6

4 10

5 15

6 21

7 28

8 36

9 45

Exited with x==10

Functions¶

A function is a named sequence of statements that performs a computation. You define the function by giving it a name, specify a sequence of statements, and optionally values to return. Later, you can “call” the function by name.

def make_upper_case(text): return (text.upper())

The expression in the parenthesis is the argument.

It is common to say that a function “takes” an argument and “returns” a result.

The result is called the return value.

The first line of the function definition is called the header; the rest is called the body.

The header has to end with a colon and the body has to be indented. It is a common practice to use 4 spaces for indentation, and to avoid mixing with tabs.

Function body in Python ends whenever statement begins at the original level of indentation. There is no end or fed or any other identify to signal the end of function. Indentation is part of the the language syntax in Python, making it more readable and less cluttered.

def make_upper_case(text):

return (text.upper())

string = "Python is going to make conducting research easier"

print(make_upper_case(string))

PYTHON IS GOING TO MAKE CONDUCTING RESEARCH EASIER

Python Containers¶

There are 4 main types of builtin containers for storing data in Python:

list

tuple

dict

set

Lists¶

In Python, a list is a mutable sequence of values. Mutable means that we can change separate entries within a list. For a more in depth tutorial on lists look here

Each value in the list is an element or item

Elements can be any Python data type

Lists can mix data types

Lists are initialized with

[]orlist()

l = [1,2,3]

Elements within a list are indexed (starting with 0)

l[0]

Elements can be nested lists

nested = [[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6], [7, 8, 9]]

Lists can be sliced.

l[start:stop:stride]

Like all python containers, lists have many useful methods that can be applied

a.insert(index,new element) a.append(element to add at end) len(a)

List comprehension is a Very powerful technique allowing for efficient construction of new lists.

[a for a in l]

# Indexing and Slicing

a = ['lists','are','arrays']

print(a[0])

print(a[1:3])

# List methods

a.insert(2,'python')

a.append('.')

print(a)

print(len(a))

# List Comprehension

print([x.upper() for x in a])

lists

['are', 'arrays']

['lists', 'are', 'python', 'arrays', '.']

5

['LISTS', 'ARE', 'PYTHON', 'ARRAYS', '.']

Dictionaries¶

In Python, a dictionary (or

dict) is mapping between a set of indices (keys) and a set of valuesThe items in a dictionary are key-value pairs

Keys can be any Python data type

Dictionaries are unordered

Here is a more indepth tutorial on dictionaries

# Dictionaries

eng2sp = {}

eng2sp['one'] = 'uno'

print(eng2sp)

eng2sp = {'one': 'uno', 'two': 'dos', 'three': 'tres'}

print(eng2sp)

print(eng2sp.keys())

print(eng2sp.values())

{'one': 'uno'}

{'one': 'uno', 'two': 'dos', 'three': 'tres'}

dict_keys(['one', 'two', 'three'])

dict_values(['uno', 'dos', 'tres'])

Tuples¶

In Python, a tuple is an immutable sequence of values, meaning they can’t be changed

Each value in the tuple is an element or item

Elements can be any Python data type

Tuples can mix data types

Elements can be nested tuples

Essentially tuples are immutable lists

Here is a nice tutorial on tuples

numbers = (1, 2, 3, 4)

print(numbers)

t2 = 1, 2

print(t2)

(1, 2, 3, 4)

(1, 2)

sets¶

In Python, a set is an efficient storage for “membership” checking

setis like adictbut only with keys and without valuesa

setcan also perform set operations (e.g., union intersection)Here is more info on sets

# Union

print({1, 2, 3, 'mom', 'dad'} | {2, 3, 10})

# Intersection

print({1, 2, 3, 'mom', 'dad'} & {2, 3, 10})

# Difference

print({1, 2, 3, 'mom', 'dad'} - {2, 3, 10})

{1, 2, 3, 'mom', 10, 'dad'}

{2, 3}

{1, 'mom', 'dad'}

Modules¶

A Module is a python file that contains a collection of related definitions. Python has hundreds of standard modules. These are organized into what is known as the Python Standard Library. You can also create and use your own modules. To use functionality from a module, you first have to import the entire module or parts of it into your namespace

To import the entire module, use

import module_name

You can also import a module using a specific name

import module_name as new_module_name

To import specific definitions (e.g. functions, variables, etc) from the module into your local namespace, use

from module_name import name1, name2

which will make those available directly in your

namespace

import os

from glob import glob

Here let’s try and get the path of the current working directory using functions from the os module

os.path.abspath(os.path.curdir)

'/Users/lukechang/Dropbox/Dartbrains/Notebooks'

It looks like we are currently in the notebooks folder of the github repository. Let’s use glob, a pattern matching function, to list all of the csv files in the Data folder.

data_file_list = glob(os.path.join('../..','Data','*csv'))

print(data_file_list)

[]

This gives us a list of the files including the relative path from the current directory. What if we wanted just the filenames? There are several different ways to do this. First, we can use the the os.path.basename function. We loop over every file, grab the base file name and then append it to a new list.

file_list = []

for f in data_file_list:

file_list.append(os.path.basename(f))

print(file_list)

['salary_exercise.csv', 'salary.csv']

Alternatively, we could loop over all files and split on the / character. This will create a new list where each element is whatever characters are separated by the splitting character. We can then take the last element of each list.

file_list = []

for f in data_file_list:

file_list.append(f.split('/')[-1])

print(file_list)

['salary_exercise.csv', 'salary.csv']

It is also sometimes even cleaner to do this as a list comprehension

[os.path.basename(x) for x in data_file_list]

['salary_exercise.csv', 'salary.csv']

Exercises¶

Find Even Numbers¶

Let’s say I give you a list saved in a variable: a = [1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, 49, 64, 81, 100]. Make a new list that has only the even elements of this list in it.

Find Maximal Range¶

Given an array length 1 or more of ints, return the difference between the largest and smallest values in the array.

Duplicated Numbers¶

Find the numbers in list a that are also in list b

a = [0, 1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, 49, 64, 81, 100, 121, 144, 169, 196, 225, 256, 289, 324, 361]

b = [0, 4, 16, 36, 64, 100, 144, 196, 256, 324]

Speeding Ticket Fine¶

You are driving a little too fast on the highway, and a police officer stops you. Write a function that takes the speed as an input and returns the fine.

If speed is 60 or less, the result is $0. If speed is between 61 and 80 inclusive, the result is $100. If speed is 81 or more, the result is $500.